Basic Information

| Field | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Keum Sook Byeon (also rendered as Byeon Keum-sook) |

| Birthplace | Central North Korea; later relocated to Hyesan, Ryanggang Province |

| Nationality | North Korean-born; settled in South Korea (from 2009) |

| Known for | North Korean defector; mother of activist Yeonmi Park; survival through trafficking and a transnational escape |

| Reported Occupations | Nurse in the Korean People’s Army; informal seamstress; coerced marriage in China during escape |

| Education | Reportedly studied inorganic chemistry |

| Languages | Korean; reportedly some Chinese acquired during/after escape |

| Family | Husband: Park Jin-sik (deceased); Daughters: Eunmi (b. 1991), Yeonmi (b. 1993); Grandson (b. 2018) |

| Key Dates | 2002–2004: husband imprisoned; Mar 2007: crossed into China; 2008 (some accounts 2010): husband’s death; Apr 1, 2009: arrived in Seoul |

| Current Life | Low-profile residence in South Korea; occasional appearances with family in public/social media |

Early Life in North Korea

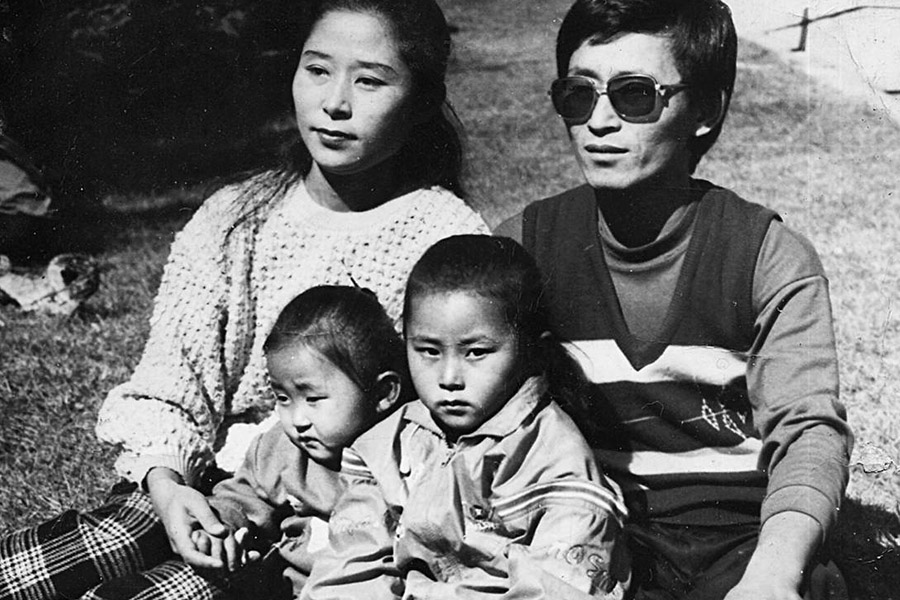

Keum Sook Byeon’s life unfolded against the stark backdrop of the 1990s famine, known as the Arduous March. Born in central North Korea and later settling in Hyesan—an austere border city in Ryanggang Province—she raised two daughters in a one-storey hillside home that often went dark and dry. Water meant walks to the river. Heat came from a small hearth. Survival was measured in firewood bundles and bowls of noodles saved for rare celebrations.

In October 1993, her younger daughter arrived prematurely, reportedly under three pounds. Doctors doubted the baby would live. The child survived, a testament to a mother’s vigilance in a time when hospitals lacked basics and winters cut to the bone. These intimate details—cold rooms, threadbare blankets, the sound of trains below the hill—color the portrait of a family improvising through scarcity.

Family Roles and Sacrifices

Her husband, Park Jin‑sik, worked as a civil servant and, like many forced into gray markets by famine, turned to cross‑border smuggling of items such as cigarettes and metals. Those illicit earnings brought occasional relief, but they also attracted danger. In 2002 he was arrested and imprisoned; he was released on medical grounds in 2004. During those years and after, Keum Sook did what many mothers did: she shielded her daughters, kept their heads down, and stitched opportunity out of a failing economy.

Reports describe her running a small sewing effort with friends, using an old pedal machine to make children’s clothing for black markets. Profit margins were thin; debts stacked up. Still, she persisted—thread, needle, and grit.

Flight Through China and Loss

In 2007, the family’s ordeal intensified. After the elder daughter slipped into China at age 16, fear of state punishment pushed Keum Sook and her younger daughter to cross the frozen Yalu River around late March. Accounts depict a night of brittle ice and heavy silence, the kind of crossing where footsteps echo like alarms.

In China, the exploitation long faced by female defectors became their reality. Multiple reports indicate that Keum Sook endured sexual violence and accepted a coerced marriage to shield her younger daughter from assault. The family reunited briefly with her husband when he later crossed the border; he was gravely ill. He died from cancer in China—some accounts place his passing in 2008, others around 2010—leaving tragedy as a waypoint on their flight to freedom.

The Gobi Trek and New Beginnings

With help from underground networks and missionaries, mother and daughter moved south through China to Qingdao, then west by train. In early 2009 they reached the edge of the Gobi Desert. The final push into Mongolia—wind, sand, and cold—was a test of will more than muscle. At the border, when threatened with being sent back, they reportedly vowed to harm themselves rather than return, a desperate gambit that led to detention and, eventually, transfer onward.

On April 1, 2009, they arrived in Seoul. It was a date to remember: the end of a 700‑plus day odyssey and the start of a new life under open skies. In time, they learned the elder daughter had also reached safety via a separate route through China and Thailand. Accounts say the family reunion in South Korea came after seven years apart—a long arc bending, finally, toward home.

Work, Skills, and Resourcefulness

Earlier in life, Keum Sook reportedly served as a nurse in the Korean People’s Army and had studied inorganic chemistry—qualifications that once conferred modest status. But qualification alone doesn’t fill a rice bowl during collapse. What stands out is her improvisational skill: cutting fabric against risk, budgeting in an economy of hunger, navigating informal markets where trust is a currency and betrayal a tax. Her resourcefulness is both domestic and strategic—caregiving, bargaining, endurance.

Life in South Korea and a Private Present

Since 2009, she has lived quietly in South Korea. Public appearances are rare and typically connected to family: a Q&A alongside her younger daughter, a mother’s day tribute, a 2017 event abroad, a visit shared online in 2023. Her life now appears steadier—enough to travel and to see extended family—yet her preference is privacy. The spotlight has favored her daughter, a prominent activist and author; the mother’s role remains largely offstage, where the most consequential acts in any family often occur.

Family at a Glance

| Name | Relationship | Birth Year | Notable Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Park Jin‑sik | Husband (deceased) | — | Civil servant; engaged in smuggling; imprisoned 2002–2004; died of cancer in China (reported 2008; some accounts 2010). |

| Eunmi Park | Elder daughter | 1991 | Escaped to China in 2007; later reached South Korea via a separate route; reunited with family after years apart. |

| Yeonmi Park | Younger daughter | 1993 | Escaped with mother in 2007; arrived in Seoul Apr 1, 2009; later became an activist and author; mother to a son (2018). |

| Grandson | Grandchild | 2018 | Represents the family’s next generation growing up in freedom. |

Selected Timeline

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1993 | Younger daughter born prematurely on October 4, reportedly under 3 pounds. |

| 2002–2004 | Husband imprisoned for smuggling; released on medical grounds. |

| Mar 2007 | Keum Sook and younger daughter cross the frozen Yalu River into China. |

| 2008 (2010) | Husband dies of cancer in China (dates vary by account). |

| Early 2009 | Mother and daughter cross the Gobi Desert into Mongolia. |

| Apr 1, 2009 | Arrive in Seoul, South Korea. |

| 2017–2020 | Younger daughter’s marriage; later divorced. |

| 2018 | Birth of grandson. |

| 2023 | Publicly noted family visit shared online. |

Themes and Legacy

To understand Keum Sook Byeon is to parse strength that rarely seeks attention. Her story is a bridge made of small planks: a sewing machine foot pedal, a child’s coat pattern, a border crossed at night, a promise whispered in a detention room. While details vary among defector accounts—a reality shaped by trauma, memory, and risk—the arc of her life points to steadfastness. She protected her daughters through scarcity and danger, accepted hardships so they might step into open societies, and built, piece by careful piece, a quieter, safer present.

FAQ

Who is Keum Sook Byeon?

She is a North Korean-born mother and defector known for her difficult escape to freedom and for being the mother of activist and author Yeonmi Park.

Where did she live in North Korea?

She was born in central North Korea and later lived in Hyesan, a border city in Ryanggang Province.

What is known about her career before defection?

Accounts report she served as a nurse in the Korean People’s Army and had studied inorganic chemistry.

How did she and her younger daughter escape?

They crossed the frozen Yalu River into China in March 2007 and, after a perilous journey, traversed the Gobi Desert to reach Mongolia in early 2009.

What happened to her husband?

He was imprisoned from 2002 to 2004 for smuggling and later died of cancer in China, with reports placing his death around 2008 (some say 2010).

When did she arrive in South Korea?

She arrived in Seoul on April 1, 2009, after detention and processing following the desert crossing.

What hardships did she face in China?

Reports describe sexual violence and a coerced marriage, reflecting the exploitation commonly faced by female defectors.

How is she connected to current public life?

She keeps a low profile, occasionally appearing alongside her daughter in public or on social media, but generally lives privately in South Korea.